I’m in the process of publishing all my book notes into this website in order to review, collect and share my knowledge database. I can’t recommend this strategy enough, because it makes easier to retain knowledge and you can refresh interesting stuff that came up when you were reading and taking hand-written notes1. While reviewing the notes of Scaling Teams2, I stumbled upon a very interesting concept I highlighted in one of the people management chapters. Let’s get into it.

Management shouldn’t be a promotion

In order to understand better why I find this framework for identifying potential managers inside your team great, it’s important to acknowledge that inside a tech company management shouldn’t be perceived as a promotion3. This is very important because if you perceive that being a manager is the only way to progress in your career, odds are that, at best, you will risk converting great engineers into mediocre managers. Promoting a great engineer into management can have two different but negative effects. You can lose a great individual contributor (IC) and you can burn out the team this person is trying to manage.

Of course this isn’t this way all the times. Maybe this excellent engineer can be an excellent manager too. Maybe he or she has some specific skills that make this person a potential great manager. How can we address this? Is there any way to hint that a member of the team can be a manager too?

Identifying traits

One of the most common approaches of identifying management potential is to search for specific traits that ICs may show in daily operations. Scaling Teams lists a couple of them:

- Mentorship.

- Communication skills.

- Empathy.

- Organic leadership.

There’s also negative traits, stuff to identify against a potential management career change:

- Stress handling.

- Problems communicating.

- Conflict avoidance.

This seems quite obvious. Who would want to select somebody who can’t communicate well as a manager candidate? Or worse, somebody who avoids conflict and can’t handle stress, translating these problems into the team. It may seem clear, but I have some problems with this approach.

Many of these traits can be a good indicator against a career change into management. But many of them are very influenced by personal situation, self-perception of conduct and current knowledge. For instance, somebody who is bad at communication skills can improve if he or she acknowledges its lack of skills and sets into an improvement and learning path. Same can be said about stress handling or conflict avoidance.

I see a problem with a traits-only approach. It’s too static, it doesn’t account personal change and improvement and it may be dependant of personal situation of the person you’re evaluating.

A better approach

Let’s not discard traits as an indicator. Let’s work with more data, with a different approach, to come up with a better decision. Enter Up-Sideways-Down framework.

Up-Sideways-Down

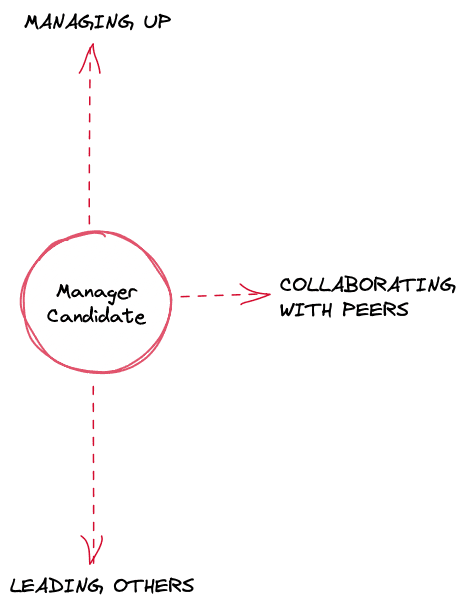

Scaling Teams authors describe a great way to identify potential managers that do not necessarily get into account a fixed photo, but more the evolution of the person.

In this framework, there are three directions that can help us to identify how ICs are helping the company, his or her colleagues and others inside the company.

Up direction

There are great examples about this up-direction indicators. Has the engineer managed to alert about a potential problem ahead in the roadmap? Or maybe an approaching deadline that won’t be met?. There are many other indicators and engineers tend to have many opportunities to give this feedback up during the development of the projects.

Sideways

This means successfully collaborating with peers in any occasion. Does this engineer work well with others in different situations? Maybe during a difficult time, maybe crediting peers, sharing responsibilities and so on.

Down

Quoting the book, this means showing leadership. I understand this more as helping others (which could be seen as leadership too). From mentoring to helping onboarding or empowering others.

Wrap-up

As you can see, traits are more like a static picture but the Up-Sideways-Down framework is more dynamic and can help identify engineers that could be missing some important traits but can improve on those with coaching and mentorship. Maybe an IC had an at-home difficult situation that made him or her incapable of managing stress for a while but was effective at escalating problems, working with others and helping onboarding new members. Or maybe somebody is lacking communication skills but showing these soft skills the Up-Sideways-Down framework helps us identify, so one clear path could be offering a management career path alongside a learning program to help communicate better.

In the end, I think these three points are the main lessons to learn when selecting somebody to grow as an engineering manager:

- Management is not a promotion. Don’t ruin a great engineer career with a management role change.

- Traits are useful, but beware bias.

- Use also Up-Sideways-Down system to have a better picture.

Scaling is hard and when a company moves from initial steps to a mid-level more mature one, management is needed in order to avoid multiple problems or management debt. I hope this small guide can help you decide how to pick and grow managers inside your team.

- I prefer this method but many others use the book margins to annotate.↩↩

- This is hans down one of the best tech management books I’ve ever read. On par with Camille Fournier’s “The Manager’s Path”.↩↩

- I talk about tech companies but I’m not qualified enough to know if this could apply to other types of companies. Could be. Or not.↩↩